1521-2021 (Part 5): Celebrating Points of View

500 years make a rare milestone for a nation or the world; and for a planet that has been populated for only about 10 millennia or so, that calls for great celebration. But it depends on where you stand or whose point of view you take: the conqueror-victor’s or the conquered-victim’s. In a world history peppered with infamous conquests, devastating wars, cruel plunders and frenzied revolutions, the narratives fall mainly within those two defined camps. As of now, various groups have rolled out programs and festivities to mark their own stakes from divergent ancestral legacies.

Spain

First is Spain, the one who started it all through Magellan. It recently reenacted Elcano’s arrival in Cebu in March 1521 through an expedition by a Spanish naval training ship which docked at Cebu Port 500 years later. The commemoration was not meant to celebrate the “discovery” of the Philippines but the first circumnavigation of the world by Elcano on board the ship Victoria. After Magellan was killed by Lapu-lapu on Mactan Island in April 1521, Elcano eventually took over his place as Captain-General of the fleet.

However, giving the honor to Elcano and his 17 trusty sailors would not be entirely accurate, for several reasons. First, Magellan had been in Malacca, Malaysia and, in fact, had come from there before he actively sought the support of the Portuguese and Spanish kings for an expedition to the East. He took the old route westward through the Indian Ocean and around Africa on his return to Lisbon in 1512. We know the Portuguese king rejected his plan, but the Spanish king approved it. Second, in 1511, Magellan had taken under his protection Enrique to be his translator and navigation aide to the islands he wanted to explore. The two sailed back to Europe where Magellan laid down the groundwork for his great enterprise with a big part to be played by Enrique or “Black Henry”, whom Magellan named after Prince Henrique the Navigator of Portugal. Why did he name him after a respected fellow-Portuguese-and-navigator?

History has somehow neglected and forgotten Enrique, a lowly indio identified as Magellan’s “slave”. Why bring along one who could not even speak Spanish or Portuguese? Enrique had lived in Malacca when the Portuguese attacked and captured the city in 1511, with Magellan being 1 of 3 captains of caravels dispatched from India for the invasion. In the following year, Magellan was reported “missing in action” and imputed with corruption – perhaps, one of the reasons he was eventually fired by the king.

Enrique, who might have been captured during the battle of Malacca, impressed Magellan for his skills in navigation and command of the languages of the surrounding islands. Whether Magellan bought or acquired him as war booty remains unresolved. We only know that he brought him to Europe as a fellow campaigner for his plan to return and find Ophir – the fabled El Dorado. He taught Enrique to speak Portuguese and Spanish. How else would they have communicated with one another and with others? A slave may be useful for certain things; but an illiterate slave who knew only his foreign tongue served no purpose in the courts of Spain. Pigafetta even noted how the Spanish monarch was impressed by Enrique’s fluency in many languages. Hardly would anyone praise a man’s speaking abilities without having conversed with him in person.

If all Magellan needed was a page, he could have had anyone from Portugal. Enrique had a great advantage over others: He knew by heart the place where Magellan wanted to go. He knew the people, the language and the customs. And he knew the place and, most certainly, how to get there. Enough evidences show that Enrique, like so many adventurous seafarers of the islands, was a skilled sailor who must have sailed from Malacca to the neighboring islands to trade.

Moreover, Magellan must have gotten firsthand information from Enrique about the presence of gold, other precious metals and spices in Ophir. It would not even be preposterous to imagine that Enrique may have worn gold in his person — decorating his teeth, as was the fashion of the natives then, or around his neck or wrist as an ornament. Gold was as common as gems and beads where he had come from. That alone could have led Magellan to see the value Enrique held for his personal ambitions. Even if he had no gold, his stories about the gold and resources in the islands must have persuaded Magellan that he had found the vein to the mother lode. So, if he was merely a Malay-speaking guide and knew nothing else about the fabled islands, he did not measure up to the effort and investment Magellan put up to showcase him. The Portuguese knew hundreds of other Malay-speaking natives, but no one else thought of doing what Magellan did with Enrique.

Bringing Enrique to the king paid off for Magellan. Besides, what better proof could he have shown the king other than gold itself, a precise route to the place and a native of the place? Short of having taken a trip to the actual place while he was in the East, Magellan only had Enrique as his best royal exhibit. Yet to our satisfaction, some sources claim he did just that. Remember the time he was missing during the Malacca conquest? It was then that he and Enrique visited Ophir and made an ocular inspection in preparation for the greatest expedition and enterprise Magellan had ever envisioned for himself and for his country, whichever it was. For having given up his former nationality out of dismay at the Portuguese king, he became a Spanish citizen.

So, if Magellan and Enrique sailed from Malacca to Ophir then back and eventually to Spain and back to Ophir, where they not then the first persons to circumnavigate the globe? Maybe not in the same ship, but they made it all the way around. As Pigafetta narrated: When Magellan sailed from the Marianas, he took a southwesterly route toward Mollucas. He knew the latitude and longitude of Mollucas (from fellow Portuguese sailors); and since Ophir was near the Spice Islands, he simply needed to do 2 things. One, to ascertain he had nearly made it around the globe, about 360°, he needed to get near Mollucas. Then, he only needed to make a short jump-off on the final leg. He must have also wanted to complete the circle for his personal claim to the honor we are giving to Elcano. It was a badge of honor any sailor would have wanted, and Pigafetta himself said in his published account of the voyage that Magellan did circle the globe.1 From Moluccas, reaching Ophir only depended on Enrique providing the final piece of the puzzle. Hence, two, Magellan had to give Enrique his own bearing so he could trace the way back home from Mollucas. Let us clarify.

For Enrique, a skilled navigator of a banka or djungga (small or medium-sized boats for 10 to 30 people), sailing on a clear night required following the North Star due North from Mollucas. Then, he would then turn west either by following the setting Sun or by reckoning from the North Star at night to reach the islands. And that is exactly what Magellan, using more sophisticated tools, took: a route due-north (about 127° Longitude just above Moluccas) then a route due-west (about 9° 40 Latitude, by Pigafetta). Originally, Magellan kept between Latitudes 20° and 28° since he had started crossing the Pacific, as Columbus had done. That would have taken them between Luzon and Taiwan and up to mainland China. However, he had a new bearing that Enrique knew based on his (or both their) real-time experiences.2 Thus, they landed on Homonhon, an island at the southern tip of Samar Island on March 17, 1521 (local date). It took two expert navigators to accomplish the most enterprising expedition in colonial history. Giving all the credit to Magellan has produced a myopic narrative.

The final questions we need to answer are: How did Magellan finally find his way to the golden islands if the Portuguese (including Magellan himself) had been there so close for many years and never found it? And why did he not show his proofs to anyone, not even to the Portuguese king, as it appears? Perhaps, he did and no one considered them credible. Also, he must have learned how Spain had rewarded Columbus, an Italian, for his exploits in the West Indies, although he missed Ophir. Magellan must have imagined himself to be worthy of more honor and reward for his eventual success. Other more compelling reasons pushed Magellan to become so obsessed with Ophir that his frustration over his rejection in Portugal pushed him across the border.

We must remind ourselves of the objectives laid in the papal bull upon which the Treaty of Tordesillas was based. It was to explore unexplored territories and to claim unclaimed regions. That treaty came after Columbus had reached the West Indies. For Magellan then, Ophir was both “unexplored and unclaimed” by any western power. He eagerly wanted to be the one to present it to an investor who accepted his crucial information. Enrique was both his prime witness and solid evidence for finding and claiming the land. Spain has all the reasons to celebrate the honor and opportunities that Magellan presented to her.

Roman Catholic Church

The next stakeholder in the mix is the Roman Catholic Church. The pope recently commemorated the first mass held in Limasawa on March 31, 2021, 500 years to the day Magellan celebrated it on an Easter Sunday. Already a fluent interpreter, a mediator and a converted Catholic, Enrique would facilitate the conversion of the King of Cebu and the rest of the local royalty and islanders. (Can you imagine if Enrique did not speak Cebuano: He would be translating the chaplain’s words or catechism-book texts from Spanish to Malay so another Malay-speaking guy can translate it into Cebuano! For many historians, it is easier to assume all the datus knew Malay.) Truly, Enrique deserves the honor and acknowledgment for his prime role in completing the journey and for promoting goodwill between the visitors and their gracious hosts. Among his other roles, he was now Magellan’s fellow-missionary, which we rarely appreciate today.

We do not suggest that Enrique be canonized or recognized as a hero; that is not our concern. Our main concern is that of properly establishing a possible alternative historical narrative by looking at all views based on available facts and deriving viable and logical conclusions consistent with a more solid and credible perspective of actual events in the past. Yet, we realize something in the narrative prevents many Catholics to accord Enrique the proper honor he deserves. In fact, the role of religion in the whole enterprise itself begs a great question.

We know how important the mass is to Catholics. Whether in the past or in the present, its role in the religious and social lives of its members is of great value in relation to their faith in Christ. In that regard, all believers, Catholic or not, share in the essential value of the Gospel to the life of an individual and a nation. Nevertheless, it must be noted that the mass is not always exclusively celebrated as a religious “sacrifice” or “offering” of faith and of penance. It could also be done for or in connection with other “intentions” or specific purposes, such as the completion of a building, a person’s birthday, death in a family, and the start or the end of a journey. In contrast, whereas Christ delivered the solely spiritual and essential importance of “worship in spirit and truth” without regard to place, form or ritual, and as sufficiently expressed through a “pleasing, living sacrifice”, the mass cannot fall within that organic or spirit-centered paradigm the Lord taught. (John 4:21-24; Rom 12:1) For Magellan and company, it equally and primarily marked the beginning of a great undertaking made possible by their arrival. They had come to do an entirely different thing not directly relevant or consistent with honoring God, much less serving His benevolent and compassionate demands.

Hence, mass, as a thanksgiving rite, extended into a proclamation and inauguration of a specific purpose many fail to understand. It was required of every expeditionary head to properly establish control, security and, it follows, possession of an unclaimed territory. Columbus did it and so did Magellan, complete with all the legal documentation and ceremonial rites required by the authority of the sovereign ruler and as attested to by a chronicler and by a priest, as representative of Vatican. The Church and State, in fact, merged in the person of Magellan, who was also a recognized catechist teacher and even taught and baptized some natives himself. His role was to establish the majesty’s complete rule over the territory from that point onward.

In short, it was not merely Magellan’s task to claim the islands supposedly for the Church, foremost, but also for the King of Spain. The mass was the pope’s symbolic presence, sealing by his authority the legality of the claim upon the islands through the king who was also a parishioner or religious subject of the Church. Just as Columbus was technically entitled to become a governor of the lands he claimed, Magellan also had the same rights and duties.3 All that came from religious and civil jurisprudence, not Holy Scriptures. Moreover, the lack of demarcation between the laws of the Church and of the State effectively placed the islands and the people under a totally foreign conception that eliminated their inherent sovereignty, rights, possessions, freedom and, thereby, forfeited their very lives.

Hence, beyond addressing all or any personal intentions of the mass-goers lay the much bigger and wider significance of the day. It signaled the establishment of a global post (religious, trading or military, etc.) at the ends of the Earth. Just as Spain had claimed lands in America, she also claimed Western Pacific Islands and ruled there for over 3 centuries. It all started with a mass on Limasawa Island.

The coming of the Spanish navy fleet to commemorate’ Elcano’s triumphant first global journey (sic) may not have been with regard to the “discovery” of Ophir; but the holding of the mass was, whether those who celebrated it know it or accept it or not. Otherwise, they would not have done so if they had known the real purpose of Magellan’s mass. He had come to do a specific job and he did it as a subject of the Vatican See and of the Spanish Crown. Regardless of his personal faith and views of Christ, his mission was to fulfill the instructions of the pope through the crown. Magellan was both the cross and the crown personified, moving as one. And Magellan wielded both with determined hands and a firm will.

The Roman Catholic Church, in celebrating what Magellan accomplished for her, must make an honest and realistic assessment of the real legacy that she had established, derived, and which they now hope to present and pass on to her adherents and to the world, in general.

Portugal

Before we forget, let us now consider Portugal’s stake in this commemoration. Even today, the two neighboring nations have something to differ about. Portugal also claims the honor of celebrating Magellan’s accomplishments as a Portuguese, if not by legal nationality, then by birth. The claim is justified for one simple reason: When Magellan first sailed to the East, he was a Portuguese; but when he came back to Europe and sailed back to the East, he was already a Spaniard! Hence, as “legally” apportioned by the Papal Bull of Demarcation of 1493, Magellan sailed Portugal’s side of the globe as a Portuguese and then Spain’s side as a Spaniard. Touché!

Hidden from many, however, Portugal has another reason to claim Magellan’s feat as its own even after he became a Spanish citizen. Magellan was undeniably a knight of the Military Order of Christ, which was founded in Portugal by King Denis in 1319 to replace the Knights Templar (which had existed from 1118 to 1312), thereby, acquiring the Templars’ assets and properties through a papal bull. In 1417, Prince Henrique the Navigator became the Grand Master of the order and ignited the spark that launched the Age of Discovery. He opened the Navigator School in Sagres and, thus, fueled the exploration and acquisition of lands by Portugal. Note that in 1433, through the king, Duarte I, the order was granted sovereignty over existing and future conquered territories. As a knight, Magellan could become a sovereign ruler abroad.

Contemporary portraits of Magellan show him wearing the cross insignia of the order. We need to point out that Henrique was both Magellan’s founding headmaster and grand master. Using that name gave honor to Enrique for his native skills and to Henrique for his visions for their order. Magellan was the bridge that linked and completed his own vision for his order, for his nation and for his religion. And so, when he planted crosses on the lands he claimed, he was not merely claiming them for Spain and for the Church but also for the Order of Christ. The rest of the knights planted crosses all over the world. The giant cross in Buenos Aires signifies the order’s historical colonial sovereignty. Magellan may not have remained a Portuguese, but he remained a bona fide knight. As a knight, he may not have taken the vow of chastity but only those of poverty and obedience (in 1492, Pope Alexander allowed knights to marry), for he got married in 1517, the year he became a Spanish citizen.

By now, we can appreciate more Magellan’s actuations. He was not merely ordering masses as a religious practice ordained by the pope, or as a legal proceeding required by the king to acquire lands, but also as a military duty coming from his grand master (who was either the Portuguese king or a prince). So, those who only see his patently pious duties as a Catholic or as a Spanish citizen fail to see other dimensions that went beyond the noble call of Christ the Lord. He was, for all intents and purposes, a free-lance Knight Templar on a crusade to recover the gold treasures of Solomon. In his case, he did not have to go to Jerusalem to recover the gold (or wherever it was then) but went to the actual source of Solomon’s gold – Ophir. He beat all other Templars in that regard.

In the point of view of Magellan, as a Templar, the whole quest was one finely calculated, planned and executed venture set long before the 15th century. 1521 was the year it all went full-circle, as literally and figuratively made by Enrique and Magellan. Henrique’s Portugal would take great pride in that.

Kapuluan

Finally, we consider the views of the people of Kapuluan then and now. In a podcast, a noted historian said that in writing our history, he would neither say the Spanish “discovered” nor “rediscovered” the Philippines. He preferred the word “arrive”. But “arrive” is appropriate and right up to only a certain point, as to a person taking a vacation. It connotes an end of a journey but fails to describe a more deeply-rooted journey or quest that has, at least, a thousand-year historical precedent. Consider the real purpose why Magellan — or Columbus, for that matter, who missed his goal by half of the globe — wanted to “arrive”, in the first place. Both explorers were in search of the gold of Ophir. Without this missing facet in the long colonial story, we will not see the interplay of those and other events that led to the global upheavals leading to 1521: the reformation, exploration of America, Treaty of Tordesillas, the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, and the Church’s need to seek a greater religious, economic and political control over so-called unexplored regions.

Magellan was only one, maybe a big player searching for “unclaimed” wealth, but just an errand boy of the European masters sitting on their thrones. They were all after the source of King Solomon’s gold. Magellan and the Portuguese were almost there but not quite, until Magellan met Enrique. Columbus, Magellan and many others searched scriptures for the route to the eastern islands (Indies). Only Magellan made it. He arrived because he was first told to go and he followed the right directions from a resident-native. He arrived, yes, but much later than King Hiram’s and King Solomon’s navies which had bought gold there more than two millennia earlier.

In tracking the route from another direction, Magellan merely confirmed scriptures and thus fulfilled his mission to the Crown. As a visitor or a tourist who thus arrived, he should have left and taken nothing. But he did not intend to simply “arrive” and trade but to stay and possess, as instructed. Alas, he stayed and was possessed by the land. Lapu-lapu claimed his body as a trophy. Pilipinos have a glorious history that was cut short, despoiled, erased, distorted and replaced by various rulers, explorers and historians after Magellan. After 500 years, the people of Kapuluan still remain in the dark. But not for long. The light filters through the cracks that we hope to split wide open.

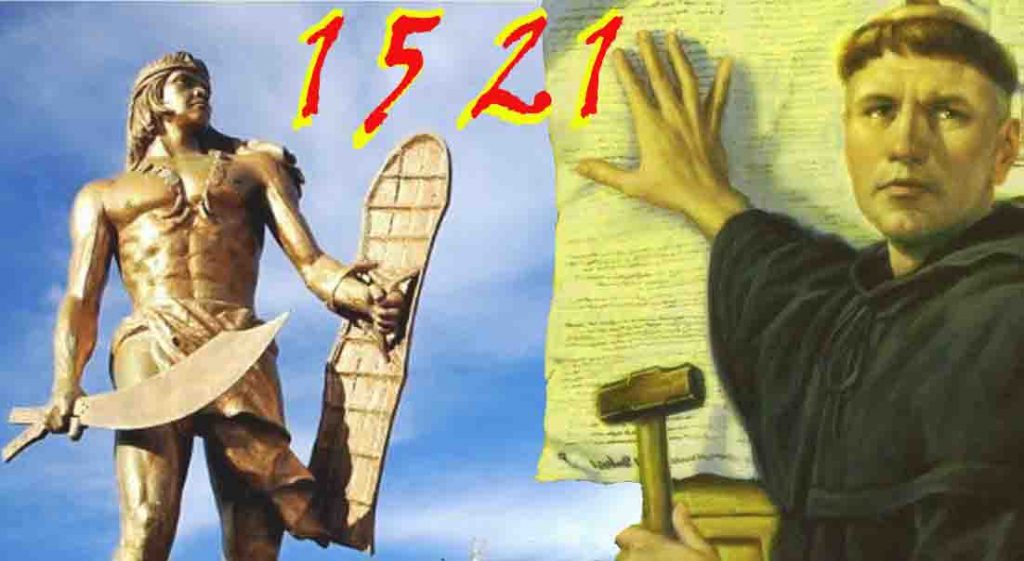

The citizens of Kapuluan have varying and diversely-conflicting views on many matters, more so with respect to this celebration. The government has expressed its rejection of the historical yarn of the Spaniards having “discovered” the islands, something that the foreign participants have duly respected. It is expected to commemorate Magellan’s defeat by Lapu-lapu in a grand and unprecedented manner on April 27. Nevertheless, the Battle of Mactan remains a bone of contention not just between secular historians but also among religious and non-religious groups and individuals.

A Catholic priest would understandably be in a bind as to how to handle Lapu-lapu, for instance. Why? Because many, if not most, of them naturally consider Magellan as the pioneer who brought Catholicism to the islands; and for a local tribal chief to kill him thus pours cold water over Magellan’s heroic feat for their religion’s cause. While many of them may have a hands-off stance on Lapu-lapu’s historic role, a few might look at him as an accidental footnote in history or, worse, a violent person who stained the goodwill that pervaded the first few “peaceful” weeks the Spaniards were in the islands.

But perhaps, no one truly recognized then the real purpose of Magellan except Lapu-lapu alone. We have shown what the real mission was. As such, the datu stood in the way of Magellan’s immediate plan to establish a military and trading post in Cebu. Having made a peaceful alliance with Cebu’s King Humabon (baptized as “Charles”) and the rest of the chieftains in surrounding islands, Magellan would not allow a rebel from a tiny island to tarnish his well-deserved prize. After all, the 1493 papal bull specifically instructed him to “convert” and to “pacify” the natives. (He must have carried on board a copy of it, as well as that of the Spanish Requirement of 1513, to read to Lapu-lapu, as was the legal practice). He had easily converted the natives, except for one single datu who would not even give him tribute of chickens and fruits or, least of all, kneel to the cross. He had been successful in regaling (and thereby frightening) the islanders with the power of his weapons and armors, demonstrating the invulnerability of their Toledo-steel armors, swords and helmets, and the thunderous power of their cannons and arquebuses during festivities. In the face of such psy-war tactics, Humabon wisely chose acquiescence as the better part of valor, as well as peace instead of war against a mighty force. Later on, he would change his approach.

Magellan definitely walked on cloud nine for over a month after he had landed. He not only marveled at the display of gold in the land, he also feasted in the kindness and hospitality of the natives. And, through Enrique’s aid, Catholicism already had a foothold. The natives readily added to their nude and crude anitos the flashy and ornate santo niños brought by the foreigners. They marveled at the novel story of the man who died on a cross and rose from death. If they could bow down before images of naked adults and fancy infants, what was another image of a naked man hanging on a cross? Perhaps, many believed the gospel and accepted another religion as it was uniquely taught by Catholics. Or many may have merely followed the lead of their chiefs. The overwhelming positive response must have pleased Magellan and his men no end.

The blood compact between Magellan and Rajah Humabon of Cebu marked a fraternal bond that Magellan must have warmly embraced. Between the two rulers and gentlemen, the act contained not just a solemn vow but also a covenant to respect each other’s rights and privileges and to promote the welfare of their followers. Later on, after Magellan’s death, the illicit treatment of married local women by the Spanish led to the dissolution of that compact. Some claim that Enrique conspired with Humabon after Serrano, Magellan’s replacement, refused to honor Magellan’s written will to set Enrique free and to pay him 10,000 maravedis (would fetch at least PHP 2.0 million on eBay today). Thus, the natives, in retaliation and out of mercy for Enrique, perhaps, offered to host a feast where they massacred some of the Spanish, including Barbosa and Serrano. The absence of real conversion or inculcation of brotherly love and kindness clearly showed through the ensuing events, which included other Spanish abuses and skirmishes between natives and the visitors in other places.4 And so, Enrique regained his freedom and got his revenge on the cruel Serrano, but not his inherited chest of Spanish coins.

Perhaps, the belligerent stance that Magellan took against Lapu-lapu led the natives to think twice about their new brothers in blood and faith. If they had not been that friendly, they would have been treated in the same way. So, were they treated kindly because they were kind as well? Or were the foreigners up to something else other than to remain as friends and brothers? Were they simple traders as they seemed to make themselves to be? At one point, Magellan admonished his men to stop trading their goods for gold (for there was plenty) in order to preserve their goods meant for the spices that they had come to procure and bring home. For many natives preferred to trade their gold with tools, such as knives, to the sailors’ delight. But to fulfill their contract, they had to bring home the required amount of spices. Gold was a bonus “discovery”, but it could be had on the next journey. Magellan displayed patience and discipline, but not his men. After Magellan died, morale and morals broke down.

So, we can see how certain realities played on Magellan’s mind. Lapu-lapu deserved to be taught a harsh lesson he did not have to apply on Humabon and others. The papal instruction to “pacify the islands” meant keeping it in peace – Pax Romana. We all know that before they arrived there was relative peace among the local tribes. Magellan brought the un-peace. For him to keep the peace, everyone had to submit to his authority. He had already claimed possession over the islands, at least, on paper and in law. Making people believe he came in peace was the easy way to achieve his ultimate goal. A chieftain looking for a fight challenged Magellan’s peaceful rule. Lapu-lapu was a pagan and an unconverted person, in the first place. To Magellan, Lapu-lapu was a hindrance to the ultimate goals of the Church and the Crown.

In short, Magellan’s decision to “pacify the islands” in the way he implemented it did not come from him but from Vatican and Spain. The cross and the crown were already firmly planted on March 31, 1521. In his mind, Magellan considered Mactan as part of his claim. So, Lapu-lapu was either to become a brother or an enemy to him. On the other hand, Lapu-lapu accurately saw Magellan as he was: a conqueror, a usurper and an enemy unworthy of allegiance. Lapu-lapu was not being proud but being realistic as the leader of a free island.

Although there were unavoidable conflicts between Lapu-lapu and some of the datus, Magellan’s own eagerness to exclusively deal with Lapu-lapu sought to satisfy the aims of the foreigners and Lapu-lapu’s enemies. An ad hoc alliance was formed to remove the common thorn on their backs. And so, Magellan put himself at the disposal of the local tribes and even led the attack on Mactan. Less than a hundred Europeans against almost a thousand or even more Cebuanos made up the battle count.

Many historians also fail to appreciate and note that Lapu-lapu, like most of the islanders, also had faith in the God of Israel. Most even mistake him for a Muslim. On the contrary, many of the islanders raised their hands and acknowledged God as “Aba” or Abba”, as Pigafetta noted. Today, Catholics even address Mary in the dialect as “Aba Ginoong Maria”, which means God or Lord Mary, which is quite absurd. That makes her equal with Abba, the Father. We know they call her Mother of God, which is even more over-the-top, so to speak. But we point this out to show Kapuluan’s historical connection to the God of Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Israel, David, Solomon, and even the Queen of Sheba long before the Spanish came. Hence, to force a native to submit to your authority as new owner of his island and his rightful spiritual leader (as Magellan may have thought) never was and never will be according to divine righteousness. Whatever religion or ethical code you apply, violence and violating others’ authority, rights and possessions do not justify destroying the life and peace of any community.

Whether Lapu-lapu deserves to become a hero of national stature is not the issue. We do not honor him for his defiance and his victory over Magellan but simply for his unique spirit of independence and courage in the face of superior might and unjust dispossession of the rights and properties of God’s children striving to live in peace and goodwill among other tribes. His view deserves telling as it might have been or, at least, as it is and it should be in the minds of many Gospel believers today. That view definitely bears celebrating at present.

Lapu-lapu ruled a small island. What was that compared to Magellan’s apparent successes as bolstered by the superior authority he bore? If his sole purpose was to trade, he could have done so among those islanders who would freely trade with him, as other nations had done for centuries. But in all fairness, his first objective was to procure goods, agricultural products and even jewelry. All were manufactured or cultured products. Gold, on the other hand, had great value in itself, as ornament and for religious symbolism. It was not only a desired metal for making icons and altar pieces but ultimately proved the historical reality of Ophir as the site of Solomon’s fabled gold mines. Yet, today, even Kapuluan does not fully grasp or acknowledge this truth which the colonizers erased from their rightful heritage.

“Discovering” and “acquiring” Ophir itself was the highest prize any nation or empire had dreamed of for centuries, more so for the Knights Templar. Lapu-lapu, to Magellan, was not even worth a barrel of firepower he had carried in his ships to pay the price of totally subduing the Queen of Sheba’s territory. Again, historians fail to infuse this fact in their analysis of those crucial events. For if Magellan believed he had found Ophir, then, he was where the gold of Solomon came from, the same gold which the Queen of Sheba (Seba, Subu or Sebu) had given to him as tribute. See how gold makes people and nations go mad? First, the Spanish, then the British, then the Americans, then the Japanese, and, finally, whoever else is blinded by greed and power.

Kapuluan, it was now apparent to the Spaniards, had tons and tons of the precious metal, along with silver, bronze, iron, marble and pearl, let alone spices. It was all or nothing from the start. And so it was for 333 years afterward. If Lapu-lapu has to be honored today, we should do so not as a hero or as a leader but as a visionary – no, a prophet in his own right. He saw the Spanish as they really were and for what they intended to do. His act of defiance is not an act of an infidel or irreligious person. He stands among the heroes of faith like King David who could not stand a giant who blasphemed the living God, or Joshua who routed the idolatrous tribes of Canaan. Magellan did not land in Canaan to conquer; he arrived in the land promised by Noah to Shem and sought to grab it for Japheth. He will stand on the Judgment Day along with his benefactors to answer for their deeds.

Lapu-lapu did not have a cross to stand between his conscience and his God, Abba. He only had his faith in God, a kampilan sword and a solemn vow to protect his people. Magellan, on the other hand, had both the cross and the sword between his conscience and God. He used the cross, by virtue of his calling and his position, to claim sovereignty over Mactan and its rightful ruler. Likewise, he used the sword, by virtue of his vows and duties, to force a tribe into submission to his assumed authority. His death came quite early on in the prolonged struggle of Kapuluan to remain free and to claim that freedom for posterity. It was only 377 years after that Ophir finally claimed back his God-given freedom from the Spanish rulers in 1898.

The Spanish Colonial Legacy in Review

In retrospect, Magellan’s defeat was not only a simple case of military miscalculation but a classic display of religious arrogance which would characterize the long series of explorers, governors and friars who would swarm upon Kapuluan for the next 3 centuries. For the reason the Spanish came finally in 1565, after several failed attempts, was because they believed they had already established their rightful claim upon Magellan’s arrival. Elcano had that specific task as the new Captain-General and replacement of Magellan. He had the papers and the concrete evidences of their claim. Official photographs and selfies were not available then; but a chronicler in the person of Pigafetta provided the documents and other written logs of their expedition, properly attested to by the Captain-Generals, their chaplain and their officers. A solemn mass sealed it. Acceptance of those evidences by the authorities in Spain was necessary to prove to other nations of their valid claim. The king would have been remiss not to accept the same evidences of the claim and as proven by the actual wealth they brought home. The Portuguese would, of course, contest the claim and indeed fought the Spanish on many occasions.

The foregone final-taking of Mactan and the rest of the archipelago would merely commence officially what Magellan had come but failed to establish. He was a veteran Portuguese-and-Spanish explorer who was dutifully playing by the rules of the colonization game. Making him to be more than he was, in spite of the religious positioning he may have represented, would only insult the lives and memory of millions who had suffered under the long, harsh colonial rule. In fact, the whole hypocrisy of the religious orders in conjunction with the unjust administration of the islands was the very reason that Rizal and the rest of the reformers sought to correct and eliminate the inhuman source of their sufferings eventually. That judgment has been delivered although it has not been fully served till now. If there is one thing we must celebrate today, it is that we can be thankful that we still exist and live as a free nation upon these islands in spite of all the immorality, cruelty and the many destructive experiences we had gone, and are still going, through under the long line of colonialists.

What’s Next?

We have presented various actual and possible views taken by real players and by historians throughout the 500-year narrative. Yes, we have taken liberty at presenting justifiable moral, legal and ethical assessments of their words and actions. We have not fully exhausted everything, but these will suffice to give anyone a wider and more viable and essential perspective of the real history of Kapuluan. Yet there is still one view that requires our attention, one of prime importance and of great significance to all. It is the view of God. Is it possible to gain such a view? Who could possibly provide us that? Only God could. We will address this issue in the next part.

Footnotes:

1”The best proof of his genius is that he circumnavigated the world, none having preceded him.” – Pigafetta (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Magellan)

2Although Enrique may have been only familiar with the south-west route from Malacca to Cebu, if he and Magellan did make that exploratory trip, that would explain why he and Magellan took Latitude 9° instead of 20°. Magellan must certainly have taught Enrique (whose namesake was Henrique the Navigator) the use of the astrolabe to allow the two to navigate directly and eventually to Cebu. (Note that his slave-navigator-translator was the second highest-paid man on board Victoria, 50% more than what Pigafetta and others received.) The main reason they landed on Homonhon, and then on Limasawa, was because the latitude they were taking led directly to Cebu where Enrique was said to have lived as a youth. Coincidence? No, the two were not navigating blindly but with exact directions from their own experiences as sailors and as confirmed by the valuable records and experiences of previous explorers, such as King Hiram of Phoenicia, Marco Polo, Vasco de Gama and the crucial information provided by ancient cartographers they used as references. Francisco Serrano, Magellan’s friend who had left Malacca for the Moluccas, provided him vital information about the location of the Moluccas. The two would later reunite for the expedition. Magellan, Serrano and Enrique were ardent heirs of Henrique the Navigator, as they diligently poured over those references in their common quest for riches and renown.

3The Spanish Requirement of 1513 (Requirimiento) was a law that required the reading of the official claim by Spain over unexplored lands. That was done by reading the law to the natives or from the ship toward the land in order to enforce the legality of the possession of the territory. (See how Columbus did it in the movie Conquest of Paradise.) And when necessary, military action was justified in order to enforce the law upon the people and the land. This law was eventually expanded into the Doctrine of Discovery and helped propel extensive exploration of unclaimed or previously-claimed regions by the European and other western colonizers, including Portugal, Britain, Netherlands, France and the US, using religion as the ideology upon which the law was founded. In the case of the US, the doctrine was relabeled as Manifest Destiny and democracy the ideological basis.

4If it is true, as claimed, that Enrique did not speak Cebuano and was not from Cebu, how did he talk to Humabon; and why would the Cebuanos give so much importance to him and even rescue him? Pilipino National Artist Carlos Quirino wrote that Enrique was from Carcar, Cebu and was fishing when he was kidnapped and taken to Malacca when he was about 14 years old. It is also said that a trading colony of seafaring merchants from Luzon Island had thrived in Malacca before the Portuguese came. Was Enrique, perhaps, not a kidnap victim after all but a resident foreign-trader in Malacca then? Whichever he was, he spoke Cebuano, Malay and, perhaps, also Tagalog and, therefore, knew how to navigate between the two places.

References:

3. The First Person to Circumnavigate the World

4. Enrique de Malacca: Interpreter ni Magellan Pilipino Ba??? (The Best and Clearest Explanation)

5. Reimagining Enrique de Malacca: Inspiring Historical Fiction Beyond the First Encounter

7. History of the Order of Christ

8. Military Order of Jesus Christ

9. First Mass in the Philippines

10. Knights Templar Exposed at Last

11. Bambi Harper, “A Look at Enrique de Filipinas/de Cebu/de Butuan,” , Phil. Daily Inquirer, March 1&4, 2003.

12. Bambi Harper, “Who was Enrique de Malacca?” Phil. Daily Inquirer, March 15&__, 2003.