The Real Da Vinci Code (Throwing Away the Bread of Lies)

(This article is taken from the latest publication available at www.manariwa.com. You may download a free PDF copy at this link: The Agape)

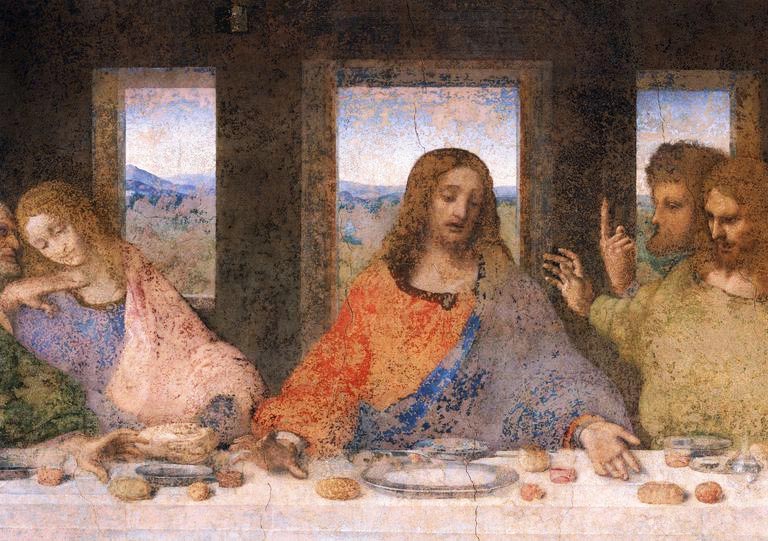

We have heard of Dan Brown’s controversial novel, “The Da Vinci Code”, romantically linking Jesus Christ with Mary Magdalene. (Although I read it, I did not watch the film – I detest fictional comedy!) One of the proofs presented to solve the puzzle in the mystery-thriller is the Renaissance Era’s most iconic mural painting, “Last Passover”, done by Leonardo da Vinci from 1495 to 1498 in Milan.

As the myth alleged, the person to the right of Jesus is not the Apostle John but Mary. We are led to believe that the physical features are clearly that of a woman and not of a man: gentle-faced, beardless, narrow-shouldered, fair-skinned, soft-flowing-haired, and with a head bent like that of a woman. Although he looks manly enough, Philip’s craned neck looks more effeminate. As we said, Brown’s tale is quite laughable at best.

The more plausible story hidden behind the painting involves Da Vinci’s engagement with the era’s raging political and religious issues and not some obscure and absurd conspiracy theory. Let us take a quick look at the milieu within which the art masterpiece was created, as well as other personalities who were involved.

In 1550, Giorgio Vasari characterized Da Vinci as having a “cast of mind . . . so heretical that he did not adhere to any religion,” in the book “Lives of the Artists“.1 The evaluation is considered unreliable as Vasari eventually removed that description from his second edition of his text in 1568. Either Vasari had acquired the impression from a false source or was eventually converted to Da Vinci’s own reformist views by then. Nevertheless, Vasari had pointed out the artist’s involvement with secret societies and alchemy in trying to show the artist’s tendency to hold unorthodox beliefs.

Freud added to the darkening of Da Vinci’s long shadow cast over history’s landscape with his psychological assessment of the artist as a “thoroughly abnormal mind”. A seemingly valid judgment of an artist who, being left-handed, wrote backward and read his encrypted writings in the mirror. Whatever might have been Freud’s basis for his conclusion, that cannot prevent many from seeing the artist’s genuine and exceptional talents as a welcome, one-in-a-billion abnormality only a rare genius can accomplish.

Born to an unmarried couple, Caterina and Ser Piero da Vinci, Leonardo was accepted and nurtured in his father’s family and quite early on developed his skills in art and mathematics. The Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio took him in as an apprentice and honed the lad’s artistic abilities.

Like his contemporary, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Da Vinci lived up to his reputation as a “heretic” and, in fact, conscientiously worked as one among many pioneers of the Reformation. We know that in only a couple more decades after he finished his “Last Passover”, the Protestant Reformation would erupt. Indeed, Da Vinci had his own religious views which he channeled clearly through his works, not the least of which is the one we now hope to consider to everyone’s satisfaction.

Firstly, Da Vinci decried the use of relics, religious art and other “holy” items as merchandise. And like most reformists, he spoke against the selling of indulgences and questioned the practice of mandatory confessions, ritualistic religiosity and the “cult of the saints”.2

Moreover, Da Vinci “assailed the clergy — at all levels — for their lack of morality, values, and education. As a scientist, he questioned the contemporary reality of miracles performed by priests and monks”.3 Artists, especially the truly discerning, are often also militant rebels. They observe more and see farther because they ponder and understand life more deeply than most people.

Leonardo invariably displayed his revolutionary views through his paintings. “He removed haloes; dispensed with the inclusion of gold, azure, and other expensive colors; avoided elaborate costumes for Mary and the (arch)angels; and presented visual meditations on the meaning of Jesus as the Christ and of Mary as mother. He found proof for the existence and omnipotence of God in nature — light, color, botany, the human body — and in creativity.”4 We can somehow say that he deliberately expressed his faith through his contemplation of the biblical narrative using his art.

It does not end there. Remember the Council at Ferrara-Florence convened in 1438? That aborted re-union of the Latin and Greek branches of the organized Christian religion, more than anything during that time, significantly influenced religious art that came out after the decree was signed. According to the Council‘s “decree of union, signed on 5 July 1439 and promulgated in Florence the following day by Pope Eugenius IV . . . in the Bull Laetentur caeli: ‘The body of Christ is truly confected in both unleavened and leavened wheat bread, and priests should confect the body of Christ in either, that is, each priest according to the custom . . . of his western or eastern church’”. Hence, the two churches peaceably agreed to allow each side to use the kind of bread they had traditionally used: unleavened for the Latins and leavened for the Greeks.5 This ambivalence, one we have pointed out in Chapter 4, would have far-reaching effect on European life and art.

So, being an Italian under the support and auspices of the Machiavellian-leaning Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza (who once bragged that the pope was his chaplain), Da Vinci would have been expected to represent bread in the commissioned mural as unleavened bread. Why did he use leavened bread instead? Was it due to an arbitrary expression of artistic freedom? Or was he, in fact, fully aware of the controversies surrounding the issue which had been revived and reconsidered around the time of his birth (when, in 1472, the Greeks officially rejected the “decree of union” of the Ferrara-Florence Council, 1438-1445) and which continued to serve as a defining bold line separating the Latin and Greek churches? As such, did he intentionally depict an inaccurate historical picture of the Lord and His Apostles eating leavened bread during Passover in order to make a statement?

After the Reformation, it would become very common for artists to use either kind of bread as pictorial aids to devotions, including works of art that were inside public church buildings. In the case of the “Last Passover”, which was rendered inside Sforza’s personal chapel, we might say that Da Vinci had more leeway to express his theological views. Even Martin Luther allowed for either kind of bread to be depicted as long as such visual aids were not seen inside churches.6 In that case, Da Vinci even had a more definite stand on the issue and not just simply depicted it but highlighted it for people to ponder upon.

Without going back to the arguments already discussed in this book, we can clearly glean a rebellious spirit impelling Da Vinci to paint his ground-breaking work according to his own intentions and his personal assessment of the issue. For although the scene itself tries to relive that moment of Christ’s revelation of Judas’ forthcoming betrayal, we cannot avoid reading that pictorial “inaccuracy” as, in itself, another sign of his unequivocal rejection of many Catholic doctrines and practices – if we are to accept he truly was a heretic! As such, the painting is not merely recalling that confused moment when the Apostles heard Him accuse one of them as a traitor; it also reminds the viewer (then and now) of the continuing betrayal of Christ by those who present themselves to be His disciples or priests. In effect, they send Him once more to the cross by their false beliefs, shallow religiosity and hypocrisy. And, indeed, through reenacting His sacrifice, they continually revive His shame and sufferings.

And so, with Jesus’ left-hand palm facing up and pointing to a piece of leavened bread, Leonardo shows Christ solemnly inviting the believer to partake of the new bread with Him in genuine faith, good conscience and pure love and not out of personal gain or an unrepentant spirit. At the same time, the right hand (right-thumb pointed directly to another loaf of leavened bread) displays tension and appears to image the left hand of Judas, likewise agitated — their opposing hands in the process of reaching into a bowl between them. (We know that the Old Testament considers the right hand as a symbol of strength and righteousness; while the left hand that of weakness and unrighteousness. Moreover, the right thumb reflects anointing or election.) Right and left. Right and wrong. Betrayed and betrayer. Da Vinci plays up the visual juxtaposition with unabashed visceral drama.

Yes, in essence, Jesus would say, “The one to whom I give the bread I dip will betray Me”; but He could also be saying, “Those who will betray Me are those who continue to consume the bread of immorality and corruption.” Yeast, as we have said, invariably pictures human depravity in the Old Testament. The fact that Da Vinci does not show Jesus holding a piece of leavened bread seems to say that Judas was undeserving of the “new and living” bread He was offering His genuine and obedient disciples.

And so, as Judas’ darkened face recedes from the light emanating from the person of Jesus, we can feel the multiple emotions bouncing back and forth between the characters in the painting, as well as back and forth between Da Vinci and the viewer.

Betrayal! It did not happen only then during that final Passover meal. It continues to happen today with the misplaced and misdirected teachings and practices of misguided people throughout the world.

We can all accept Leonardo Da Vinci as being both a “heretic” as well as one having a “thoroughly abnormal mind”. Also, as a compulsive artistic genius who adhered to no religion – particularly the ones that hold sway over the masses. Even today, he would be branded or pilloried as an eccentric par excellence and non pareil. No matter. As it has been said, “Social history and art history are continuous, each offering necessary insights into the other”7 Political and social realities do influence art, in general; but, now and then, art – the enlightened kind – can turn the table around and redirect the flow of human history. Dr. Jose Rizal’s fictional novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, did exactly that – it led to a nation’s independence.

Da Vinci did not live and create within an artistic vacuum, unlike many people today who mindlessly churn out selfie images as fleeting as a fluttering butterfly, seen this moment and replaced by another, equally ephemeral, in the next moment. It took him three years to paint it; but the feast he depicted took about 1,300 years to be cherished and commemorated by a small Middle-Eastern nation and another 1,500 years to be fulfilled, replanted and celebrated in the hearts of faithful men and women worldwide until the Renaissance Period. In essence, Da Vinci painted a timeless obra maestra of an unchanging and eternal message which majority of people have missed fully comprehending for two millennia.

Still not convinced by Da Vinci’s influence on art history? “Prior to about 1500 most depictions of the Last Supper (sic) in Western art showed unleavened bread on the table, but since then leavened bread has usually been shown. This change involved the abandonment of what was understood at the time to be a historically-accurate representation of the Last Supper (sic), in favor of a historically-inaccurate one.”8 The real “Da Vinci Code” has a deeper and a far more important and enduring significance. Just like Christ, Da Vinci was pointing to the New and Living Way ushered in by Pentecost Day, around AD 33, and not to the Old and Dying Way of Passover.

Most people today do not know this. But now you do.

Next time you visit Milan, see this great painting and celebrate art like you never did before – not with the Bread of Lies but with the True Bread of Life. Or better still, when you are with fellow believers, partake of the Bread of Life in pure, simple and joyful celebration.

Endnotes:

1http://www.beliefnet.com/entertainment/movies/the-da-vinci-code/leonardo-his-faith-his-art?p=2.

2http://www.beliefnet.com/entertainment/movies/the-da-vinci-code/leonardo-his-faith-his-art?p=2.

3http://www.beliefnet.com/entertainment/movies/the-da-vinci-code/leonardo-his-faith-his-art?p=2.

4http://www.beliefnet.com/entertainment/movies/the-da-vinci-code/leonardo-his-faith-his-art?p=2.

5”Depicting the Bread of the Last Supper: Religious Representation in Italian Renaissance Society,” Journal of Religion and Society, The Kripke Center, Vol. 11 (2009), p. 9.

6”Depicting the Bread of the Last Supper: Religious Representation in Italian Renaissance Society,” op. cit., p. 13.

7”Depicting the Bread of the Last Supper: Religious Representation in Italian Renaissance Society,” op cit., p. 1.

8Ibid., p. 1.

(Painting above courtesy of www.google.com)