Guess Who Else Attended the Last Passover? (How Leonardo da Vinci Got into the Picture)

Putting his compositional skills to work 110% on the “Last Passover” required Da Vinci to use his extensive grasp of Mathematics, Science and Literature. As a visual artist, he possessed an almost magical, mythical or mystical comprehension of physical nature, human nature and even divine nature. Blending all three into a seamless illustration of one of the most monumental events in human history has qualified him to become not just a great artist but also a prophet in his own right.

For what is a prophet but one who upholds and proclaims the truth? Through this revolutionary masterpiece, Da Vinci regales us with how his “abnormal mind” (Freud) wove lines and colors, light and shadow, and thoughts and emotions to highlight his “heretical” (Vasari) views on Christianity’s most divisive and controversial doctrine.

Seated second from the left is Da Vinci’s representation of Apostle James the Less. It is obviously a self-portrait of the artist. However, unlike most artists who “get into the picture” merely for fun, Da Vinci uses himself to emphasize the importance of the historical event, as well as its continuing significance. He was not going to comment visually on something that was of infinite value to humans since the time of the Creation until the Judgment Day without himself participating in – or partaking of — the wonder and the glory of it all. And what better way to experience the moment than to be among history’s most colorful, most revered and most contemplated personalities, as Christ and the Apostles are? At least, virtually, as we all do today through touring the world via Google Earth.

And so he painted himself into the Last Passover. How he did it is a compelling story in itself.

Art has the power to draw us into the story being portrayed. An art work is itself the mind of the artist. No, it is his soul and his life. In portraying the life of Jesus Christ and encapsulating what He meant to humans and to the painter, Da Vinci sought to bring into focus all the virtues that He ever preached and practiced and which He also strove to instill among His disciples — and all people, for that matter. Love, peace, perfection, obedience, salvation, providence, security and faith. And to serve as counterpoints to those virtues, he also had to bring in unbelief, betrayal, sacrifice, submission, suffering and death.

But before we highlight those sublime ideas, let us look at the physical process Da Vinci undertook to synthesize his views and talents into one compelling piece of art.

Da Vinci clearly divides the 15-foot-by-29-foot frame into five congruent triangles, consisting of Christ’s near-perfect triangular body-shape in the middle and four groups of Apostles, each group forming a rough triangle. Except for Christ, the perfect Being, the geometric configuration is done subtly. The number 3 (III in Roman script) is repeated further in the three windows behind Jesus, serving as backlighting mainly for the figure of Christ, as well as to render depth to the whole painting. Here, Da Vinci replaces the ubiquitous halo of previous artists with “real” light coming from the sky. Notice that no one else shares that center-window illumination with Christ – as the Light and Life of the World, He alone deserves the honor.

The question of where to place himself exactly in the picture must have largely occupied the artist’s mind. Where would you put yourself, if it were you? For Da Vinci, the painting’s layout was a mathematical problem that required a mathematical solution, as well as plenty of aids from Physics, particularly Optics.

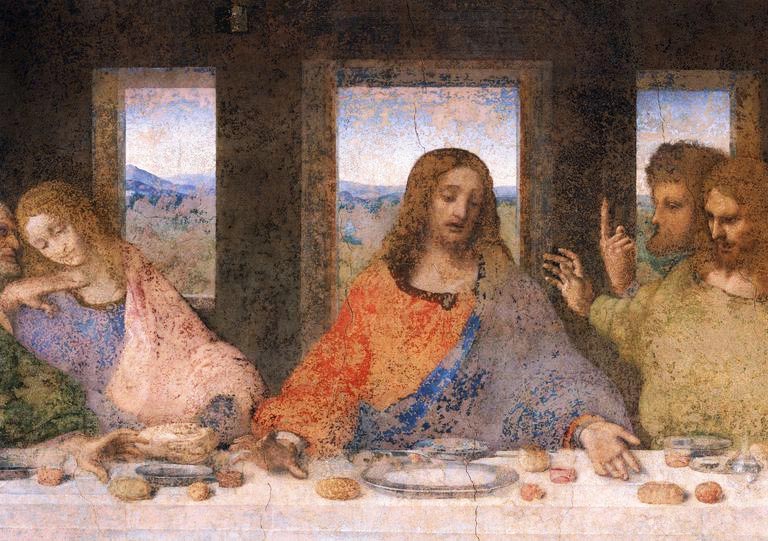

Consider the meaning of his surname: Da Vinci – of the conqueror. He knew every Christian was a conqueror and that the Lord Jesus was THE CONQUEROR (VINCI). V is the Roman symbol for 5. So, he placed a V on each side of Jesus: one formed by John and Jesus, on the left, and the other by James the Great and Jesus. Notice also that each letter V would point directly down to His two hands (and 5 fingers) — the left hand offering the leavened bread and the right struggling to confront Judas. With His left hand He would conquer those who will believe His teachings by wielding the Truth; and with His right hand he will conquer the unbelievers by dispensing judgment. His eyes look down on the bread to emphasize His mission of saving humans through His pure, life offering. He is the true Bread of Life after all.

Moreover, Christ’s hands form an inverted V or 5, which in Greek is Alpha or Λ, the Beginning. But where is the Omega or Ω, the End? Where else but at His hair that curls on both sides, replicating an Omega letter. There, on top of each other are Alpha and Omega right smack on center!

Now, if we count Christ’s position in the array, He will be 7th (or VII) from the left and also from the right. Seven, being the perfect number of Creation, puts Him right at the center of all things. Whether you look at the painting directly or from a mirror, Jesus will remain on center – the center of Da Vinci’s life, who was left-handed and wrote in reverse, readable only to others through its mirror image. In order to make his preferred position more meaningful, he subtracts the V or 5 from Christ’s position and comes up with II or 2. Exactly where he puts himself, as James the Less. But that is not all. If he looks at the painting in the mirror (or count from the right), he will be at position XII/12, which is V/5 plus VII/7 So, on either side of Jesus (directly or in reverse), Da Vinci is V or 5 steps away. Note that Da Vinci’s initials are all multiples of 5: L(50), D(500), V(5). Adding up, we get 555, where the three V’s or 5’s are in center. The whole painting seems to be a gigantic signature of Da Vinci with Christ as the hallmark.

In addition, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 are prime numbers; and twelve (also made up of four prime numbers in Roman letters – XII, where X or 10 is actually a graphic mix of two V’s, end-to-end) is a product of three prime numbers: 2, 2 and 3. The series, 1-2-3-5-7-12, consists of a sequence that Da Vinci might have used in incorporating natural aesthetic proportions into his artistic concepts.

The symmetry, along with the various contrasts in the Last Passover, reflects the balance and order in God’s physical Creation and redemptive Mission. There is light and darkness, holiness and evil, righteousness and unrighteousness, life and death, glory and shame, and victory and judgment. The artist has chosen well his personal seat at the Table of the Lord. What now was his position with respect to His teachings?

Up to that point in Christ’s ministry, everything was merely symbolic — or a prototype of what God intended to do. And as far as the Jews were concerned, the Passover was simply a commemoration of a historical event that realized their national freedom from Egyptian slavery. To Christ, however, the final Passover would picture His ultimate and real sacrificial act that would effect the freedom that humans can have from sin and death. The bread and wine, as we know, would become His flesh and blood, offered on the cross.

But first, Judas had to betray Jesus. The gang of 13 had been together as a tight group for three years by then. The time to scatter the sheep had come. Jesus was now forcing the issue on Judas; and He wanted to prepare the rest of them. He now divulged the plot of one of His close followers to betray Him. Perhaps, because of this, we should be calling this painting “The Accusation”.

Jesus had to spoil the feast and the fun. A painful lesson had to be taught. A bitter pill had to be swallowed. For Him, especially, and for everyone else.

Confusion arose. The twelve Apostles are suddenly broken or disorganized into four distinct groups of three, each group with a small story to tell and each character another inner dimension. In the middle is the One Lord, alone and serene, except for his tensed right hand that He motions toward Judas, the culprit.

To the far right are three seemingly-detached disciples (Matthew, Thaddeus and Simon) whose only connection to the scene are their perfectly-drafted hands and fingers all pointing to Jesus, with Matthew’s right hand stretching far across the other group, effectively providing a leading line toward the center of the scene. The story in this small scene is of apparent unbelief: What is He saying? This cannot be true! Do you believe this? It’s not me; who could it be?

Right beside Jesus, to His left, are Thomas, James the Great and Philip, all eyes on the Lord and engaging Him directly. Thomas, pointing to Heaven with his index finger almost next to Christ’s face, seems to provide a premonition of his doubtful heart: Unless I put my finger on it, I will not believe, Lord. James seems to look at Jesus’ right hand and waiting to see who He will point to as the betrayer: Go ahead, Lord, tell us who. Philip, on the other hand, humbly pleads, “It is not I, Lord; you know very well.”

To His immediate right is the most interesting triad of all: John, Peter and Judas. John looks almost asleep as he hears Peter whisper, “Ask Him who it is.” Peter, a dagger in hand, looks angry (as he always seemed to be) that such an accusation should be leveled during that festive time. Why this talk of betrayal; I am willing to fight and die for You, Lord! Through all this, John casts an attitude of indifferent resignation to the obvious truth: Sure, I can ask Him.

Judas recoils at the accusation, clutching the coin purse with his right hand and motioning to Jesus with his left hand: Oh, so You know; but do you have to tell them now, too? I have to find a way out of here. Jesus would give him a gracious way out. The accusation was after all meant to remove the unwanted person and to go on with the real program of the night. Jesus would then dip a piece of bread and give it to Judas, the sign given to reveal the betrayer to John. That “betrayal bread” he would return to Jesus in the form of a “betrayal kiss”.

Adding to Da Vinci’s cunning manipulation of characters and their emotions, he juxtaposes Peter and Judas by reversing their positions. Whereas Peter should be 4th in the row, he now moves toward John, making him 5th. As a result, Judas, who should have been 5th is now 4th. In doing so, the two form a letter X – a cross. The betrayer and the denier beside each other – one would send Jesus to the cross for 30 pieces of silver, the other would deny Him three times as He goes to the cross.

Finally, we have Bartholomew, Da Vinci, ooops, James the Less and Andrew, all in the process of just standing up and all eyes on Jesus. Bartholomew props himself on the table and appears to crouch toward Jesus: For what reason, Lord? Who would do such a thing? Not I, certainly! Andrew raises his hands in surrender and surprise: What? Betray? Forbid it, Lord!

James the Less, channeling the artist’s vicarious thoughts and emotions, seems to allay everyone else’s confusion, fears and doubts. He holds Andrew’s shoulder and, likewise, reaches out to touch Peter’s shoulder in order to calm his friends: Silence, let’s wait and listen.

Da Vinci, in taking on James’ position, is seriously contemplating that moment. The painter creates the moment according to his own level of faith; and he sees himself assuring everyone — and us — that Christ knows what to do and will act according to the Father’s will. He sits there painting – or partaking of the Passover – meditating on the real significance of the Person, Work and Life of Jesus. And that is how he perceives the beauty, the power and the glory of Christ. That majestic view deserves a no-less-than-perfect representation through his prodigious artistry. We all greatly benefit from and are truly humbled by the artist’s mature faith and exceptional skills.

This is Leonardo Da Vinci’s wonderful legacy. But there is much more to his story, which we will deal with in another time. For instance, why did he use leavened bread instead of the required Passover unleavened bread? The answers will amaze us all.

(Painting and drawings courtesy of www.google,com)